Tales From Tunisia

Gary Hill

Handing the 'Lonely Planet Guide to Tunisia' over the counter at the outdoor pursuits store, the assistant checks the title looks up at me concerned and asks “Is it safe?” “Well I wouldn’t be going if I didn’t think so” was my reply. It was a strange question indeed for a store whose clientele includes people who enjoy hanging off 200 metre high sheer rock faces with apocryphal names like Resurrection, Spectre and Cenotaph Corner, located halfway up the mountains of Eryri. I was in Algeria at the start of their civil war in the early 1990s and I recall feeling much safer than I’m sure I’d feel with my life in the hands of 10mm thick nylon ropes and twist lock carabiners. Heights are most definitely not my thing. I seriously doubt travelling alone for a week or two in Tunisia doing nothing more onerous than taking photographs and getting blisters from walking too much could be likened to “an activity productive of terror in the reasonably sane”, as Jim Perrin, one of the grand old men of British rock climbing, once described his chosen pastime. As it turned out I was right.

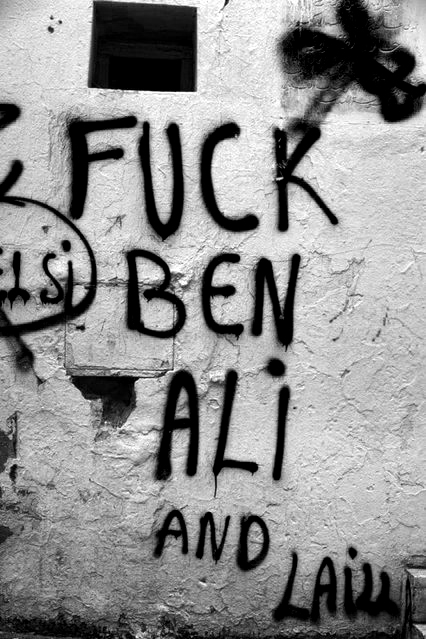

True, at the cusp of 2010-11 there had been four weeks of civil unrest that had toppled the 24-year old government of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Dissatisfaction had been brewing for years but the catalyst was a wholly unexpected event that mirrored similar past events; in Vietnam in 1963 when 66-year old Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc, poured petrol over himself which he then set alight at a busy intersection in Saigon to protest at the persecution of Vietnam’s predominantly Buddhist population at the hands of the minority Catholic government, and again in Czechoslovakia in 1969, when 21-year old student Jan Palach burned himself to death in protest of the demoralisation of the Czech people following the Soviet invasion the previous year.

That President Ben Ali, his wife Leila, and their extended familes were corrupt is surely disputed by no-one in Tunisia or elsewhere. Just using the term ‘The Family’, with it’s obvious mafia connotations, leaves no Tunisian in any doubt as to which family you are referring to. I was told that half the personal wealth in Tunisia could be linked to either the Ben Ali family by blood, the Trabelsi family of Ben Ali’s wife,or their close friends. Forty-eight members of the two families had extensive business interests as varied as banking, TV and radio stations, telecom and internet providers, to real-estate development, agriculture, car dealerships, retail distribution, an airline and even marble quarries. When Ben Ali and his entourage eventually fled Tunisia, hoping to relocate to France (who refused to let his plane land), then to Saudi Arabia (where he was granted asylum), he was estimated to have embezzled $US17 billion into various tax havens throughout the world. This is in addition to the 1.5 tonnes of gold ingots on board the flight that Leila had just appropriated from the vaults of the Banque de Tunisie with the help of her private militia. A week after their arrival in Jeddah the Ben-Ali’s travelled to Mecca for the Umrah pilgrimage, dutiful Muslims despite what Allah had decided for them.

It was Ben Ali’s ambitious, ruthless and manipulative wife who was the most despised member of ‘The Family’. Widely referred to as the ‘Lady MacBeth’ or ‘Imelda Marcos’ of Tunisia, she was the daughter of a humble fruit and nut vendor and a maid in a hammam. Brought up alongside ten brothers in the Tunis medina, she became a hairdresser, was married to a small businessman for three years, followed by divorce and a series of relationships with wealthier Tunisian businessmen, finally meeting Ben Ali, the newly appointed Director General of National Security. Becoming pregnant, she gave birth to Ben Ali’s first daughter while he was married to his first wife, who he divorced on achieving the presidency after orchestrating a bloodless coup in 1987. He married Leila in 1992 while pregnant with her second child. Rumour has it that she faked the results of an ultrasound to convince Ben-Ali that she was carrying a son, knowing he would be more likely to marry her. She had another daughter.

She and her family took immediate advantage of the marriage. Each of her siblings received a monthly pension and were given free access to the presidential palace. She arranged to have one of her elder brothers, Belhassan, divorce his wife to marry the daughter of influential businessman Hedi Jilani. Belhassan effectively became the second most powerful man in Tunisia after Ben Ali, and came to rule over the rest of his family like a mafia don. He proceeded to manipulate the Tunisian stock market and speculated wildly in real estate. On setting up an airline, Kathago, he routinely had spare parts stripped from aircraft of the government owned national carrier Air Tunisia. He was then made a member of the board of the Banque de Tunisie where he flagrantly manipulated decision making in favour of his own and ‘The Family’ interests. Leila later cemented her hold on power by arranging to have her daughter Nesrine marry Sakher al-Materi, the son of an influential and wealthy family with a pharmaceutical empire. The young Sakher al-Materi had a meteoric rise to power with investments in the media, financial services, automotive, shipping, real estate and agriculture. It is said that Al-Materi was involved in another relationship at the time. However, after a visit from the police his then girlfriend immediately left Tunisia to live in France. Using the police to intimidate rivals was a hallmark of the Ben Ali presidency.

Leila’s nephew Imed Trabelsi had a controlling stake in the Tunisian construction industry, in addition to operating the Tunisian franchise of the French home improvements retailer Bricorama. In 2006, Imed had his own nephew, Moaz, steal a multi-million euro yacht from Corsica which Moaz sailed to a marina near Tunis. The yacht belonged to the head of the influential Lazarus investment bank, Bruno Roger, who brought legal action against the pair in France. Unfortunately for him, the French court ruled the trial should take place in Tunisia. Imed Trabelsi was charged, but unsurprisingly was found innocent by a Tunisian judge. Although the yacht was returned to Roger, Interpol issued arrest warrants for both Imed and Moaz. In 2011 Moaz was arrested in Rome and later sentenced to six years jail for a number of other yacht thefts from Italian ports.

Also in 2011, Imed was sentenced in Tunisia to two years in prison without the eligibility of parole and fined 2,000 dinars for drug possession. His case was a prime example of the change in attitude in Tunisia, not just because he was found guilty, but because the judge that sentenced him was the same one who had set him free five years earlier. He was the first member of the ‘The Family’ to serve time in jail. At his appeal the hapless Imed watched the court double his sentence to four years and add another 1,000 dinars to his fine. Later the same year he was sentenced to a further 18 years for fraudently writing cheques worth more than €300 million. Arrogantly, he began a hunger strike in protest.

A month earlier Ben Ali and Leila had both been sentenced in absentia to 35 years in jail and fined 91 million dinars (€45 million; $59 million; £37 million) for systematic theft of the public coffers, though it seems unlikely that Saudi Arabia will ever agree to any extradition request. Nesrine and her husband fled to Paris where they live in several suites of a Disneyland hotel accompanied by an entourage of staff. She was sentenced to eight years in jail and fined 50 million dinars in absentia for illegal real estate acquisition. Belhassan and his wife fled to a house they own in Montreal and have applied for refugee status in Canada.

Financial corruption were not the only despotic acts performed by ‘The Family’. Political dissent was not tolerated in any form. Two examples in the last year or so of Ben Ali’s reign show the petty and vindictive nature of the treatment meted out by a president in fear of his own people. Shortly after performing a 30-minute stand-up routine which spoofed Ben Ali and several members of his wife’s family, comedian Hedi Oula Baballah was a passenger in a car which was stopped by police and found to contain drugs and counterfeit money. Very few people in Tunisia believe that these were not planted by police on Ben-Ali’s instruction. Baballah was sentenced to a year in jail and fined 1,000 dinars. After serving six weeks of his sentence Ben Ali pardoned Baballah and he maintained a very low profile for the remainder of the time Ben Ali was in power, leading to reasonable speculation that his release was conditional on his not further criticising ‘The Family’. An example of one of Baballah’s scandalous jokes: President Ben Ali gets stopped by the police for speeding when out driving by himself. He tells the officer that he is Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, the President of Tunisia, but the cop says "never heard of you" and arrests him. At the police station Ben Ali shows his ID card and the custody officer says, "Its OK. You can let him go. He’s related to the Trabelsi's."

Less well treated was Slim Boukdhir, a freelance journalist and correspondent of the Al Arabya newspaper, who had written an article critical of Ben Ali’s family. He was abducted by unidentified men who dumped him near a park stripped of his clothes, having sustained serious injuries. Returning home after hospital treatment his house was surrounded by security forces who denied access to all visitors for four days. Soon afterwards, after writing another critical article, Boukdhir was arrested for not carrying his ID card and ‘insulting’ a police officer. He also received a one year sentence, which he served without pardon.

Ironically, the Tunisian martyr who heralded the ‘Jasmine Revolution’, not only within Tunisia, but ultimately in the ‘Arab Springs’ of Egypt and Libya, was a man not unlike Leila Ben Ali’s own father. Twenty-seven year old street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi had been continually harrassed and had his fruit and vegetables repeatedly confiscated by town officials in the small city of Sidi Bouzid. The last straw came on December 17th 2010 when he was assaulted and his electronic scales were taken. Some reports state that he was also slapped in the face by a female official something, as an Islamic male, he found particularly demeaning. He went immediately to the town hall and demanded the return of his scales. When he was refused a meeting with the local mayor he poured petrol over himself in the foyer and set it alight. Although he survived the immolation he never regained consciousness and died of his burns two weeks later on January 4th. Ben Ali had visited Bouazizi in hospital and promised his family he would send him to a specialist burns unit in France for treatment but this was never arranged. Bouazizi subsequently received the 2011 Sakharov Prize for Human Rights and had two squares named after him, one in Tunis and one in Paris. There are currently plans for two films to be made about his life.

The respect shown for Bouazizi by Tunisians is surprising given that suicide is strictly forbidden in Islam. The Islamic view on this is unambiguous; our lives are not actually our possessions, we each simply hold our life in trust for Allah, making human beings not fully independent entities but merely trustees acting on behalf of Allah. Although some Islamic pundits do have a more lenient attitude to suicide, towards those suffering severe depression for example, stricter interpretations of the Qur'an emphasise that there are no excuses. In this view Paradise is always forbidden for those committing suicide. Referring directly to events in Tunisia a fatwa from theologians at the highly influential Al-Azhar mosque in Cairo reiterated that "suicide violates Islam even when it is carried out as a social or political protest”.

This attitude may appear to negate the validity of suicide bombings but the particular brand of convoluted reasoning made possible only by theologians argues otherwise. The term ‘suicide bomber’ is considered a misnomer brought about by a ‘western’ style of thinking. The primary purpose of someone strapping a bomb to themselves and causing it to explode is not to kill themselves but rather to kill as many enemies of Islam as possible. Their own death is viewed as a necessary sacrifice and so they become martyrs. Allah will thus be pleased with their confidence in Him and their conviction of belief, therefore, they cannot reasonably be called ‘suicide bombers’. The logic of this view may be somewhat sound but the morality surely stinks to high heaven (sic). This peculiar attitude to suicide is compounded by the view that such an individual who is unfortunate or inept enough for the explosion to occur before he reaches his intended targets, or who otherwise fails to kill any infidels, is deemed by some Islamic pundits to have actually committed suicide and will not proceed to Paradise. Convoluted reasoning indeed.

My first venture outside the budget hotel I had booked into in Tunisia’s third largest city, Sousse, brought me face to face with another aspect of humanity with which Islam has considerable difficulty. An early morning stroll along Bou Jafaar Beach attracted a local guy of about my age (mid-50s) who came walking toward me smiling away as if he had found a long lost friend. He spoke very good English and enquired in the mock friendly yet exasperatingly nosy manner commonly encountered in the tourist haunts of developing countries; “where are you from?, in which hotel are you staying? is this your first time in Tunisia?, are you not with your wife?, have you been to the medina? I’d be happy to show you around.... etc etc”. Having had plenty of experience over the years with what are ultimately thinly-veiled attempts to make some money from tourists, I answered him politely and offered only as much information as I thought he may need to feel placated.

Every developing country I have visited has a seemingly endless pool of underemployed guys utilising a local brand of one-line catchphrase ultimately aimed at extracting money from the inexperienced tourist. India has a plethora of ‘tourist guides’ available to show you around, no charge of course! An added ‘bonus’ is that they all have a cousin who owns a carpet store, or perhaps makes jewellery. In Morocco every town and village has a ‘Berber Festival’ which happens to be “today only, I can take you there”. Of course, should you agree you can be sure you will pay a visit to “the carpet shop of my cousin”. Tunisia’s catchphrase is “Hello, don’t you remember me? I am chef/waiter/barman at your hotel, I would be happy to show you my city”. Rest assured, he too will have a cousin who is a purveyer of fine carpets. I naturally assumed, therefore, that my new friend’s ulterior motive was to acquaint me with the small businessmen in his extended family, but he seemed far more interested in my wife and why she was not accompanying me on my travels. We strolled further along the beach chatting together and, at the point where his curiousity seemed sated, he turned to me, put his hand on my shoulder and suggested we “go somewhere else together, somewhere quiet, we have a nice time”.

Many years ago I ran a food store which attracted a wide cross section of people including many members of the gay community. Chatting to a lesbian couple one day I asked them why they and their friends tended to shop at my place and not at one of my competitors. They looked at me a little nonplussed. “Because you’re gay” was the straightforward answer. I truly felt like I had let them down when I broke it to them that I was straight. Their laughing reply? “We honestly all thought you were gay!”. I’m pleased to say that my coming out appeared to make no difference to their subsequent food purchasing arrangements. Years later I told my wife this story and she remarked that she could understand why some people might think I was gay. I remain bemused.

I suppose most people have been propositioned by someone of the same sex at some point in their lives and I’m certainly no exception, but I didn’t expect it to happen with the first Tunisian male I spoke to at any length. I’d heard a few stories of travellers being propositioned in hammams but never on a beach. After letting him down lightly, he sauntered off, a little embarrassed, I think. I continued my walk, eyeing possible ‘Kodak moments’ rather than the local men. It got me thinking though, that it was a brave thing he did, publicly with someone he didn’t know, in an Islamic country. Attitudes to homosexuality in Tunisia don’t exactly flounder in the dark ages as in Saudi Arabia or Iran, they are relatively liberal for a Qur'an-based culture. But they are certainly less than enlightened, probably resembling most English-speaking countries in the 1930s with homosexual acts, even in private, punishable by up to three years jail. Tunisia has yet to have any public figure acknowledge their homosexuality, no political party or politician has ever shown support for gay rights and no organisations represent the gay community. It’s a typical religious-based ‘pretend it doesn’t exist’ social climate.

Ironically, much of the cafe culture in Tunisia, at least those establishments frequented by the twentysomething crowd look, to the Western European eye at least, somewhat gay. Young men in Tunisia tend to dress with monotonous regularity, in all dark clothing. Their dark hair, all styled similarly short, their ubiquitous wearing of dark sunglasses combined with a generous bristle of fashion statement stubble presents them as an army of George Michael wannabes. The fact that these guys invariably sip their coffee in groups sans women only serves to cement this image. Indeed, if you were to teleport a Tunisian coffee shop full of young males and have it appear in any city in Europe, passers-by would no doubt assume it was the local gay cafe.

I had one further gay related encounter a few days later. On arrival in the pictureque coastal town of Mahdia and walking from the train station to the medina, a lanky youth of about 16-years sidled up alongside and made the requisite enquiries as to my nationality and hotel arrangements etc. After broaching the subject of the whereabouts of my wife he asked me outright “are you gay?”. My response was “No, should I be?” The look of horror on his face was comical as he emitted a ridiculously long drawn out “No-ooooooo!!”. Whether he was actually gay, sizing me up as a possible trick, or just plain nosy I’m not certain. It’s just not the sort of question you’d expect to be asked from someone you’ve known for all of two minutes.

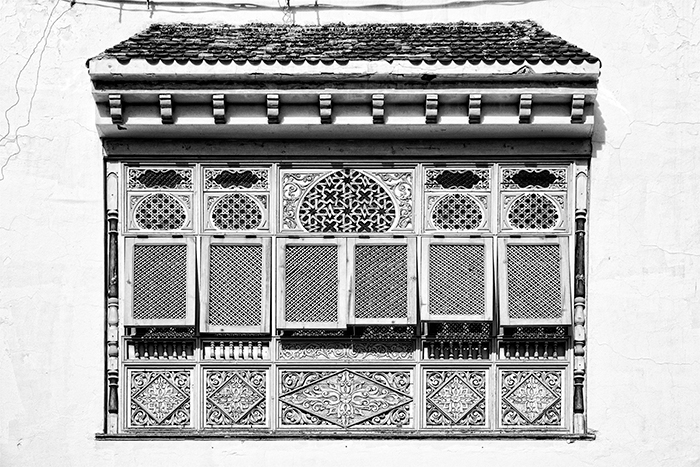

I stumbled upon a further ‘pretend it doesn’t exist’ Tunisian attitude to human sexuality while wandering around the maze of alleys that comprise the medina in Sfax, Tunisia’s second city. Unlike the old towns of Spain and Portugal, Tunisians rarely leave the front doors of their houses open. Walking past a few surprisingly open doors in an alley no more than two to three metres wide I started to notice that the inner steps to the second floor where all bathed in pink or red lights. Not expecting to see a version of the red-light district of Amsterdam in Tunisia I simply didn’t make the connection at first. It didn’t dawn on me until, when walking past one such doorway, a not unattractive woman in her thirties very gently wrapped her arm around mine and giving me a smouldering look started to walk me upstairs.

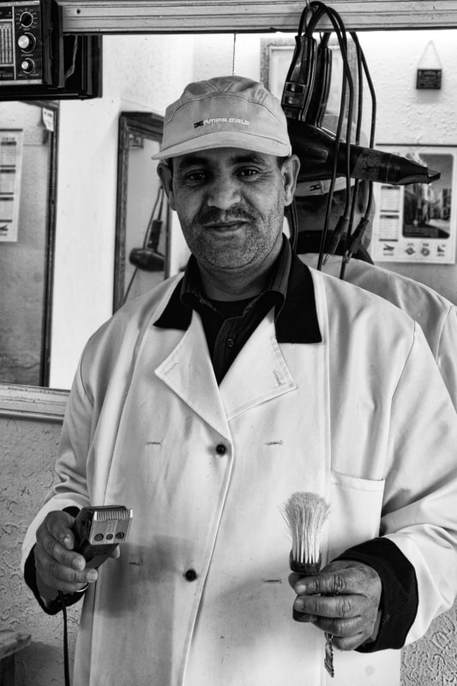

And it really was gentle. Unlike the vendors of tourist trinkets, carpets and clothing in the tourist areas there was no verbal hard sell here. Though it was a blatant attempt to have me part with my money the approach could certainly be labelled affectionate. Another charming attempt to have me part with my cash was experienced courtesy of a barber in the medina in Sousse. Now I’m bald and what hair that does survive clings to the sides, so I usually shave myself once a fortnight to a 3mm length. I had my fortnightly shave by the medina barber who then posed proudly upright for my photograph, brush in one hand clippers in the other. The very next day he spotted me walking past his shop and, leaving his seated customer mid-shave, proceeded to offer me the very same service as the day before at just half the cost, all the while looking concerned at the state of my head, pointing out tiny anomalies in the pattern of hair growth. And then again the day after.........

After politely declining my would-be lovers offer of gratification I walked back down the few steps she had accomplished, back into the alley and noticed, again for the first time, the string of men of all ages just hanging around, all silent and embarrassed like schoolchildren who’d been told to keep the noise down. What surprised me most, though, was that they all completely ignored the infidel with the big camera around his neck blatantly checking them all out. They could easily have ganged up on me and stolen my camera, money, credit cards, whatever, yet they just totally ignored me, even though I stuck out like a sore thumb. As I turned a corner taking me away from the red light houses, a boy aged perhaps twelve years offered me, in broken French, the services of his mother or his sister for ten dinar (about £4 / €5). Relating my story to two young French guys in the hotel bar who had travelled extensively throughout North Africa, their first question was “êtes-vous circoncis?”, accompanied by a snipping action made with index and middle finger and youthful sniggering. What is it about Tunisia that people have to feel they must ask questions of a sexual nature to people they have only just met? It transpired, however, that those of us fortunate enough not to be circumcised would nevertheless be unfortunate enough to be charged double should a woman's services be sought. Islamic prostitutes obviously need to maintain their standards, though I wonder what they would charge a Jewish punter?

Another fairly common sight in the cities is the fifty-plus western women, generally Dutch, German or French, though with a smattering of British, partnered up, arm in arm, with Tunisian guys in their twenties. This seems entirely uncontroversial. It’s a sort of reverse sex tourism to that of say Thailand. Some young guys actually make a sort of living out of it. They have their food and drinks paid for, a few gifts of clothing etc. and on the same day their sugar mommies go back home, a new planeload arrive. Most likely a win-win situation if care is taken.

The reason I hadn’t initially noticed the men hanging around outside the brothels is probably because the sight of men hanging around doing nothing is a common sight in North Africa. Go to the centre of any village, town or city and the streets will be full of men with seemingly nothing to do and nowhere to go. Unemployment and underemployment remain the prime indicators of the economy despite serious efforts to generate income from tourism and foreign investment in industry. Inward investment has come particularly from France and is simply a means by which companies can cut costs, pay lower wages and repatriate their profits. This is understandable in a market economy mentality. What I do find difficult to understand, however, is the ubiquitous sense of fatalism that many people seem to have, the all pervasive notion of ‘insha'Allah’. It’s not so much that you hear people actually saying it (though you do), it’s the resulting sense of apathy that inevitably results from a worldview that no endeavour is worth trying unless it pleases Allah (how on earth would you know?) or that nothing at all happens unless Allah wills it.

One of the most despicable consequences of the ‘insha'Allah’ mentality is something I have observed in several Islamic countries. In Europe, if an ambulance races up behind other cars, siren blaring, lights flashing, drivers will readily perform the trickiest of manoeuvres, mounting kerbs at traffic lights etc., to let it pass. Not so in Islamic countries, where the ambulance and the fate of the person inside will often be ignored, ‘insha'Allah’. At a more mediocre level, you will often see groups of men (and it is always men, women are obviously too busy with the household chores) standing around with nothing to do while skiploads of litter swirl around them in the breeze. This is because outside of the ‘zone touristique’ there appear to be no litter bins. Rubbish is even strewn around immediately outside establishments such as small businesses and cafes where the proprietor has obviously gone to some effort and expense to make the place look smart. On the other hand, two of the most commendable institutions in Tunisia are the universal healthcare and mandatory education systems. Despite this the numbers of children not attending school is obvious. During any schoolday you can guarantee to see kids riding on the back of scooters and donkey carts, tending the family goat or sheep herd, just walking along the road, doing anything but getting an education. Nothing emphasises the gulf between a developing and a developed country more than the attitude they have toward educating it’s upcoming generation.

“What did the last driver charge you?” he taxi driver asked. “Three dinars” I replied, even though I had no clue, as I hadn’t caught a cab in Tunisia before, though I knew they were considered famously cheap to a European resident. It was simply the amount that came into my head. If only all financial transactions were this easy. “OK”. So I jump in next to the driver and he steers the car into the flow of traffic – without first looking in his mirror, of course – causing a line of cars to screech to a halt and play a cacaphonous urban symphony on their horns. It was soon afterward that I noticed the unmistakeable sound of a wheel bearing needing replacement. About that moment the fun started. A scooter ridden by a guy in his thirties, easily identifiable with no helmet, roared close alongside the drivers side and a shouting match kicks off.

It's always struck me that both Irish and Scottish Gaelic are the finest languages in which female vocalists can sing passionately. Women singing whispered romantic songs in French definitely have the edge over other languages. Italian is indisputably the natural language for a baritone to woo his lover in a totally implausible operatic plot. And Arabic is arguably the finest language available in which two testosterone fuelled men can have an argument. The deeply resonant tones and rapid fire delivery marked by a generous overlapping of points made ensure that you are in no doubt as to the seriousness of the ritual.

Enough coins for a good three-course couscous and chicken dinner for two, with wine, came hurtling through the window, smashing against the dashboard and windscreen. I’d never seen legal tender used as a weapon before, especially in less developed countries where they’re usually trying every ruse to get you to part with your money rather than throw it at you. My driver picked up the nearest coin and threw it back with all his might, missing the benevolently violent scooter rider and hitting a parked car. I wonder whether billionaires behave in a similar manner? While us mere wage slaves might have pillow fights for frivolity, causing feathers to rain down on our heads, do those with mega-bucks beat each other over the head with wads of notes, causing dollar and euro bills to rain down on their coiffured heads?

We came to rest at traffic lights for a moment only. Before I could open the door and extricate myself to make other travel arrangements, Tunisia’s answer to Laurel and Hardy turned onto the Avenue Habib Bourguiba (every town has one) with my driver leaning out of his window repeatedly punching the scooter rider in the stomach who, riding left-handed and wobbling perilously, was attempting to return punches of his own. The whole scene was reminiscent of those old fashioned clown acts with the clown car riding around the circus arena while they all fall off, chase the car and climb back on. Car and scooter collided several times even as we drove past the female traffic cop who appears to be a permanent fixture directing the traffic on the corner of Rue Massicault.

She is certainly a sight I have never seen before in an Islamic country. She is very tall and slim with short jet black hair. In fact she was the only woman I saw in Tunisia with short hair. Strikingly beautiful, and I cannot empasise the words striking and beautiful enough, she wears an unfeasibly tight uniform of grey trousers and jacket with a rather kinky looking small grey cap balanced on her head. She goes about her work in a decidedly no-nonsense fashion, forcefully striding toward lucky miscreants punctuating the air with short sharp blasts on a tin whistle invariably followed, her point made to the errant driver, by a majestic swivel of hip and buttocks, releasing butterflies in my stomach every time. The whole scene is like a carefully choreographed dance and I found it impossible to walk past without stopping to admire the performance. The pistol on her hip only adds to the pervasive air of sexual allure; get her under studio lighting (if only) and she would have been Helmut Newton’s dream model. If ever a woman has taken advantage of Tunisia’s relatively (for an Islamic nation at least) enlightened attitudes to women, she is that woman. I doubt very much whether any man tells her what to do. Especially when he’s driving a car. I had been forewarned that photographing police officers would land me in dire trouble, so unfortunately I am left with memories only.

Generally speaking women fare better in Tunisia than in most Islamic countries. Ironically, a man is to thank for that; Habib Bourguiba (he of the boulevards) who, in 1956, became the first president of an independent Tunisia. Indeed, he is probably the only Islamic leader ever to have ‘The Liberator of Women’ etched into his lavish mausoleum in his birthplace, now the burger bar and pizza joint tourist ridden town of Monastir. He veered toward secularism and was wary of the power Islam held over the Tunisian people, preventing the country from modernising industrially and socially, having oft been quoted as referring to the hijab and niqab as ‘”an odious rag”. Bourguiba attempted to counter religious influence in three ways; by closing many madrasas (religious schools), by abolishing Sharia law and courts and by the Personal Status Code of 1956 which gave women equal citizenship status to men, ended divorce by the male simply being able to renunciate the marriage, banned arranged marriages and polygamy, and set seventeen as the minimum age for marriage for both sexes. Updates to the code within the past decade gave women further rights to property ownership on divorce and statutory rights to maternal leave from work.

The choice of western styles of dress (usually without a headscarf, albeit modest in other ways) for the majority of Tunisian women is marked in comparison to nearby Algeria and Morocco where it is generally confined to the wealthier, more westernised families. Nevertheless the hijab and niqab has been making something of a comeback with younger women in the past decade or so. Whether this is due to the worldwide resurgence in fundamentalist Islam or simply a temporary fashion statement inspired by the growth in satellite TV stations from other Arabic nations I cannot say. The latter I hope.

Scooterman sped off into the distance ahead of us. Because of the timing of his arrival I had assumed this was a road rage incident caused by the taxi cutting him up as he joined the flow of traffic on Rue de France. I could be wrong about that. Turning to me my driver pointed toward the receding speck in the distance and, while grinning like a Cheshire cat, announces with enthusiasm, “my brother!” Now whether this was a family feud or just a dysfunctional family or whether he was simply using the standard Islamic term for another Muslim I do not know, but what would likely cause psychological trauma to many people seemed to be quickly forgotten as we proceeded to make small-talk (in a combination of three faltering languages) in the unique way that taxi drivers and hairdressers worldwide are so well versed.

That night in the hotel’s bar-restaurant, after finishing my couscous poisson, I was making headway with a bottle of Magon Majus, a surprisingly good and to be recommended Tunisian red wine. Described by one British expert as “a pleasant, smooth and subtle taste with notes of forest fruits and a hint of vanilla, a beautiful length and pleasant rounded finish” and by my own relatively untrained palate as “surprisingly good, a bit like a Rioja without the oak barrelling”. I noticed one of the two business suits with i-Pads straining his neck to see the cover of the book I was reading. I tilted Daniel Dennett’s ‘Darwin’s Dangerous Idea’ in his direction (owned for at least 10 years and never yet read). His face lit up and he dismounted his stool and strode toward me arm outstretched for a shoulder wrenching handshake followed by what I can only imagine was a discourse on his appreciation of evolutionary theory along with a strident criticism of the official Islamic version of events leading to the diversity of species. I say ‘imagine’ because he was already on his second bottle of wine and spoke French with an accent I had yet to encounter anywhere in the world. Not that it mattered much, my own spoken French is ‘trés peu’ at best and my Arabic confined to a few dozen words, none of which could be used to convey ideas from the life sciences. His apparently teetotal mate looked on, visibly embarrassed. I too was surprised that he had made his thoughts known so loudly and in so public an arena.

There are growing parallels between Christian and Muslim attitudes toward evolution. Unlike the Bible however, the Koran contains a relatively incomplete chronology of creation. In particular, the ‘six ayums’ it supposedly took Allah to create the seven firmaments plus the Earth do not equate to the six days outlined in Genesis. Ayums tend to be defined as developmental stages, each of which is of an indeterminant time. Thus the notion of an old Earth and so the time required for species to diversify is, on the surface, compatible with Islam. Similarly, some Islamic commentators have likened verses in the Koran to descriptions of the Big Bang and expanding universe. A surprising number of early Islamic scholars produced texts that anticipated both abiogenesis and modern evolutionary theory. The prolific Arabic author Al-Jahiz (c. 776-869), for example, in his seven-volume 'Kitab al-Hayawan' (‘Book of Animals’) suggested a form of Lamarkian inheritance in which environmental factors caused a ‘struggle for existence’ resulting in the survival of stronger bloodlines by the transmission of inherited characteristics. Later, the tenth century Syrian poet Abu al-Ala al-Ma'arri (973-1058) composed a work in which minerals transformed into plants and plants into animals while the Persian scientist Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201-1274) outlined a notion of evolution not unlike that of the 20th Century Catholic scientist, philosopher and priest Pierre de Chardin. Al-Tusi considered that the universe initially consisted of equal and similar elements. However, internal contradictions began to appear, resulting in differences between elements. These elements then evolved into minerals, then plants, then animals, and then humans. This evolutionary process was claimed to result from individual variability to adapt to environmental contingencies. Humans were deemed by al-Tusi to be at an intermediate level of evolution with any further evolution taking place in a spiritual dimension, whatever that means. In the 19th century, after initial hostility, the later writings of the Islamic political activist and commentator Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897) pointed out that Islamic scholars had long written about evolutionary principles. He himself came to accept Darwin’s findings but he was unable to acknowledge that they applied to human beings also. More recently the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam have promoted modern evolutionary theory in it’s entirety albeit with deist underpinnings.

Nevertheless, at the grassroots level modern evolutionary theory has struggled to find acceptance in Islamic countries. In 1882 Edwin Lewis, recently appointed Professor of Geology and Chemistry at Syrian Protestant University (now the American University of Beirut) was sacked for giving a commencement speech in which he quite innocuously described Darwin's findings as ".....an example of the transformation of knowledge into science by long and careful examination." To their credit, several faculty members resigned in protest. Such was the resistance to this burgeoning new field of science that an Arabic translation of Charles Darwin's 'Origin of Species' did not appear until 59 years after its original publication in England in 1859 and only then comprised the first five chapters. Before that, simplified and often inaccurate translations of articles about biological evolution were available from 1876 via the Egyptian literary journal 'al-Muqtataf' ('The Digest'). Many of these articles carried the flavour of theistic evolution and teleological processes, translating 'natural selection' as 'nature's elect' and 'evolution' as 'further development'. Even these popular science articles were viewed with suspicion, however, and, partly because they sourced many articles from British journals, the joint founding editors, Ya'qub Sarruf and Faris Nimr were accused of being un-Islamic and unpatriotic to the Arab cause. Given the Arabic penchant for claiming the work of other cultures as their own (the philosopher al-Kindi (803-873), for example, claimed that the Ancient Greeks, along with their scientific and philosophical knowledge, were descended from Arabs) it probably did not help al-Muqtataf's popularity a great deal when the editors, in reply to a letter pointing out the history of evolutionary thought in Islamic cultures, replied that Darwin's notion of natural selection "was not known among the Arabs or the Persians or anyone else.......otherwise scientists today would not have ascribed the theory to him." 'al-Muqtataf' was finally shut down following the overthrow of the monarchy by Egyptian nationalists in 1952.

Ignorance of evolutionary theory was not confined to science, however. While British authors such as Joseph Conrad, H.G.Wells, George Eliot and Arthur Conan Doyle wove stories around evolutionary themes or at least alluded to them in their plots, evolutionary themes are notable by their absence in late 19th and 20th century Arabic fiction. And so, not surprisingly, strong resistance is still found today in the Islamic world; not one of Richard Dawkins' books are available in Arabic translation, for example. A study conducted in 2007 by Salman Hameed, Professor Of Integrated Science and Humanities at Hampshire College and published in ‘Science’ found that as few as 8% of Egyptians agreed with the statement that evolutionary theory is probably or definitely true, rising to 11% of Malaysians, 14% of Pakistanis, 16% of Indonesians, and 22% of Turks. As with fundamentalist Christians, more fundamentalist Muslims are increasingly rejecting evolutionary theory in favour of an explicitly creationist view. Although the silliness of young earth creationism is notably absent and Muslims generally have respect for scientific endeavour, many do find the link between evolution and atheism to be disturbing.

This discrepancy between evidence and faith has been used to particular advantage by the Turkish creationist author Adnan Oktar, who writes under the name Harun Yahya (though some claim this is the joint pen-name of several authors). While I saw no books on evolutionary theory for sale at all in Tunisia, even in cities, I did find a number of outlets for Arabic translations of Yayha’s writings, available gratis in small stalls set up outside mosques at prayer times. If Yahya were not Muslim and not an ‘old earther’, he could just about take the place of almost any Christian fundamental creationist wingnut with access to the media. First, he has no qualifications in the life sciences, he didn’t even finish his degree course in philosophy. Second, he associates with creationist organisations that are named so as to appear to be legitimate scientific bodies; the ‘Science Research Foundation’, for example. Third, he consistently misrepresents evolutionary theory, both scientifically and philosophically, in particular by his dogged insistence that not only is evolution claimed to occur wholly by random events or chance, but also by ridiculous assertions like “Darwinism, which holds that life has no purpose, is an invitation to suicide”. Fourth, he has offered a prize of 10 trillion Turkish lira to anyone who can produce a single intermediate form fossil. Fifth, he considers evolution to have “laid the groundwork for Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin” (but apparently, not the Taliban) and considers academics who teach or research evolutionary theory to be ‘Maoists’. Sixth, he considers acceptance of evolution to be a religion. Seventh, he has repeatedly attempted to use legal means, with some success, to get literature dealing with evolutionary theory banned in Turkey, and similar web and blogging sites blocked. Eighth, he’s been accused of sexual impropriety. You get the drift, I’m sure.

For good measure, however, Yahya not only adds an Islamic-friendly spoonful of holocaust denial to his barmy pudding, but seriously claimed in a 2008 interview in the German magazine ‘Der Spiegel’ that “Muslims who commit acts of terrorism are really atheistic Darwinists trying to discredit Islam”. My favourite quote though, comes from his website:

“Darwinists employ a hypnotic technique that prevents people from thinking independently or examining the true scientific evidence. The reason millions of people have been misled by Darwinism for years is that they have, either knowingly or unknowingly, been taken in by this spell”.

Priceless.

Enjoying a cappucino at the cafe opposite the Grand Mosque in Sousse I saw the little handcart being wheeled along and both the free and the very reasonably priced books being put on display a half-hour or so before afternoon prayers began. The serious, informed profile of Harun Yahya adorned several covers. I watched for a quarter of an hour as the faithful walked across the square and into the mosque and what struck me most was not only how few worshippers there were but also their sheer diversity. In Morocco and Algeria, worshippers are plentiful and they tend not to dress in too western a fashion. In Marrakech, for example, lunchtime prayers in the Kasbah Mosque are attended by hundreds, with males spilling out into the street, lying full length on the footpath outside the main entrance, facing Mecca. They are invariably either dressed in traditional djellaba or, for males, something like dark trousers with a plain white shirt. In Tunisia, although available, djellabas are rarely worn by any but a few elderly men and women. Those men responding to the adhan or ‘call to prayer’ in Tunisia are generally dressed in the popular dark coloured conservative and modest western style. Surprisingly, though, there were some teenagers in clothing that would not be out of place in any western suburb: basball caps, sneakers, t-shirts with brazen logos. And, a little disturbing perhaps, young men in army boots, army fatigues and t-shirts with Arabic writing. Not serving soldiers, definitely a fashion statement. These are a minority to be sure, but they are a ubiquitous minority.

The guy outside the mosque selling and giving away his wares particularly attracted my attention. He looked like Jesus. Or at least what Jesus would have actually looked like and not the blondish haired blue eyed myth of myths so beloved of white skinned Christians who have never quite come to terms with a saviour who would certainly have looked like a long-haired rag-headed hippy from those countries we have a tendency to invade. This guy looked to me like the real deal, long dark hair, black beard, djellaba with hood up, sandals, serene yet serious expression. He would sure have been one popular guy with many of the alternative lifestyle women at Glastonbury or the Burning Man Festival. Yet my Jesus (or Isa in Arabic) lookalike was, neither saviour, nor hippy, certainly not Jewish, but a purveyer of Islamic texts outside a mosque gate. Disseminating peace and love, maybe, but undoubtedly ignorance, primarily. I turned to the two Western dressed guys who ran the cafe, nodded at the bookseller and said something like “Il ressemble à Isa!”. I think they knew what I meant. At least they both laughed heartily. One of them suddenly looked aghast at his watch then ran toward Jesus at the mosque gate. “Late to pray”, his companion explained.

Listening to the majority of Christians talk about Islam you could easily get the impression that the two religions had nothing whatsoever in common, but nothing could be further from the truth. Take Jesus himself for example (the mythical one, not the guy outside the mosque gate). Belief in Jesus as a messenger of God is actually a requirement of being Muslim and he is referred to in the Koran as al-Masīḥ, ‘the Messiah’ and, as with Mohammed, mentioning his name is invariably followed by the phrase “peace be upon him”. A large portion of the Jesus mythology is believed; the visitation of Mary by an angel, the virgin birth, which is one of the most unambiguous teachings of Islam (Mary is actually mentioned more times in the Koran than the Bible, indeed she has a whole chapter named after her. Interestingly, Jesus is always referred to as the son of Mary, despite the patronymic Islamic convention), that Jesus was incapable of sin, that he performed miracles, including raising the dead, that he himself rose from the dead and ascended to God and will one day return to the Earth, ‘Insha'Allah’. The Koran actually refers to Jesus a grand total of 25 times, all in respectful terms, while Mohammed manages a meagre four mentions.

It would arguably be better for those of us who value rational thought if Islam was antithetical to the myth of Jesus. The Islamic adulation of Jesus gives succour to those Christians seeking an interfaith dialogue. On the surface this may appear to be a calming influence on the current sociopolitical situation. However, while fundamentalist Islamic clerics might regularly and aggressively push the infidel line, appeasement is an attitude readily exploited by anti-science creationists like Harun Yayha. His influential appeal for unity, for example, does not stop at theology. As he states:

People with true faith, who abide by the religion of the Prophet Abraham and believe in the one Allah must combine their strengths, grow deeper in faith and grow even stronger in unity in order to wage an intellectual struggle against the atheist, Darwinist system that is trying to rule the world”.

Yet creationism viewed as an objective science as opposed to an interesting mythology is a fundamentalist Christian doctrine. It could be argued that some threads of Islamic fundamentalism would not have become as popular as they have if it weren’t for inputs from fundamental Christianity. Arguments used by Haryun Yahya, such as lack of transitional fossils, the impossibility of functioning intermediate forms, the alleged unreliability of dating methods, and the statistical improbability of evolution at the molecular level are all cloned from American ‘creation research’ literature and simply given an Islamic flavour. The result has been that increasingly throughout the Islamic world, even in semi-secular Tunisia, whenever science and religion collide, it is increasingly science that is expected to genuflect before faith.

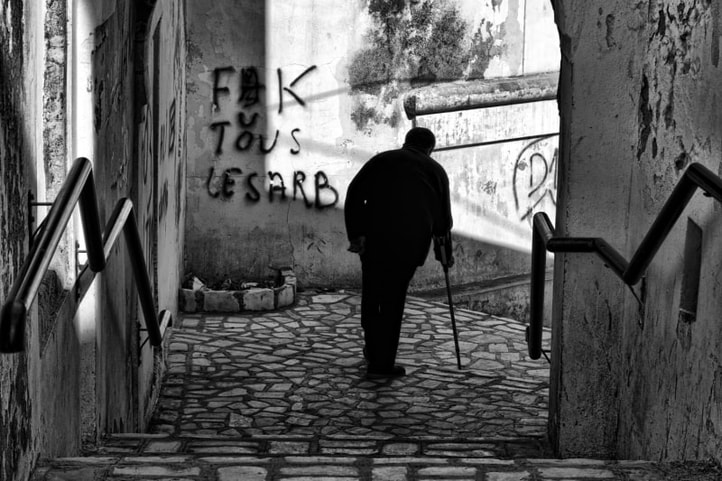

After Tunisia’s first democratic elections at the end of 2011, the moderate Islamist party Ennahda, formerly banned from participating in politics, emerged as the clear winner, achieving 90 of the 217 parliamentary seats (another moderate Islamist party, Al Aridha Al Chaabia won a further 19 seats). Ennahda have stated that they “are not going to use the law to impose religion," and intend to keep Article 1 of the 1956 constitution which states that "Tunisia is a free, independent and sovereign state, its religion is Islam, it’s language is Arabic and it is a republic”, and further, that “there will be no other references to religion in the constitution”. This reasonably innocuous decision, however, has angered many ultra-conservative Islamists, particularly supporters of the Saudi-inspired Salafist Party. They feel betrayed because while in exile for 22 years in London, the then leader of Ennahda Rachid Ghannoucci, though widely considered to be a liberal Muslim, had nevertheless sometimes advocated a strict application of sharia law to reverse the influence of western decadence. Indeed, he has an anti-Western pedigree writing that "secularism is turning the West into a place of selfish beasts". He supported Saddam's invasion and annexation of Kuwait as well as, unusually for a Sunni Muslim, giving long-standing support for Iran’s Islamic revolution. A further image problem for the prospect of continued semi-secularism in Tunisia is that the despised, and now largely deposed elite, were traditionally the country’s strongest supporters of secularist ideals.

Whether parties like Ennahda and Al Aridha Al Chaabia are genuinely committed to maintaining a degree of secularism in Tunisia or hypocritically pragmatic in an attempt to maintain economic ties with the west remains to be seen. One small businessman I spoke to feared that Ennhada had much stronger Islamic goals than they are portraying, and were simply biding their time while exercising ‘Taqiyya’, or the Islamic right to lie to infidels, whether Tunisian or foreign. He also suggested, however, that if this proved to be the case it would not be successful as Tunisians no longer feared dictators and would not hesitate to rise up again, so Islamic parties like Ennhada must be careful to remain democratic. On the other hand, another restaurant owner told me that he thinks it inevitable that Tunisia will become Islamist and be governed by Sharia law “just like Iran is”. I am further heartened then, to have met the guy who shook my hand because I was reading a book by Dan Dennett.

Whatever their real intentions, Ennahda’s current public profile contrasts strongly with neighbouring Libya who later overthrew the Gaddafi regime with the military aid of the UK and France. Here, Moustapha Abdeljalil, the senior member of the National Transition Committee, proclaimed, in his first speech after liberation that “as of now, Sharia is the upmost form of law in the country; conflicting regulations will be overruled”. One of their first decisions was to reinstate polygamy.

Unlike Ennahda, the Tunisian Salafists are not well organised politically but are fast becoming an increasingly vocal conservative voice, with enormous influence in some regions due to their religious and charitable work. A recent government statement claimed that approximately 400 of Tunisia’s 5,000 mosques were under the direct influence of Salafist imams. In recent months, Salafists have attacked synagogues, threatened women who own businesses and women wearing skirts, albeit mostly in smaller towns. In cities they have demonstrated in support of female university students who have been refused access to lectures while wearing the completely veiled niqab, and actively intimidated male and female academics wishing to maintain the ban. In true Taliban-style they demonstrated in Tunis against the celebration of World Theatre Day 2012, assaulting actors and destroying musical instruments. Other demonstrations have targeted the presence of tourists in Tunisia. On both occasions protesters waved the black and white ‘caliphate flags’, associated with al-Qaeda and the Afghani Taliban, respectively.

The important and unpalatable point to make here is that very little activity of this nature occurred in Tunisia before the ‘Jasmine Revolution’. The removal of Ben-Ali and his myriad hangers-on has had the effect of increasing the divide between secular and Islamic attitudes in Tunisia. If ever a country can be seen as a barometer for the effect of religious pressure following the Arab Spring it is semi-secular Tunisia. Thus if Tunisia ultimately evolves from the semi-secular despotism of Ben-Ali to the full-blown theocratic despotism of Islamic fundamentalism what hope is there for Libya, Iraq, Egypt and Syria?

'Tales From Tunisia'. Original images and written content © Gary Hill 2012. All rights reserved. Not in public domain. If you wish to use my work for anything other than legal 'fair use' (i.e., non-profit educational or scholarly research or critique purposes) please contact me for permission first.